Project Details...

This series was commissioned by WaterAid and shot in April and May 2015. The images are currently being exhibited at London Bridge City Pier from the 6th June to 2nd July 2015. Details here... http://bit.ly/1T5wR1K There are more images to come in this gallery so check back soon. During my research into water and sanitation in Victorian Britain, I found no shortage of records detailing the appalling living conditions in cities and towns across Great Britain. My photographs here focus on London and Manchester in particular - not because their stories are unique but because the challenges they faced were some of the greatest. From a lowly cesspit in Soho in London to the Longdendale Reservoir Chain in Derbyshire - the world’s largest water project of its time - his photographs represent just some of the dramatic changes to water infrastructure and sanitation that took place during the 19th and early 20th century. With the industrial revolution came rapid population growth and increased urbanisation. Many towns and cities across the UK experienced a huge increase in pressure on infrastructure, housing and the environment. Rivers and water courses deteriorated rapidly and in many places became little more than open sewers. Water borne diseases were rife and took the lives of thousands of people - primarily the poorest and most vulnerable. Questions began to be raised about the state's role in public health and sanitation. City officials faced huge challenges in securing a clean supply of drinking water and finding a way to deal with the ever-increasing quantities of sewage and wastewater. It took foul smells, squalid conditions, countless lives and the vision of people like Sir Joseph Bazalgette in London and John Frederick Bateman in Manchester to bring significant and lasting change. Local and national government were forced to make difficult decisions and to invest in costly infrastructure projects and research. The results of which not only brought considerable improvements to the quality of life at the time, but continue to benefit millions of people all across the country to this day.

Thirlmere Reservoir, Cumbria

In 1874 John Frederic Bateman advised the Manchester Corporation that the supply of water from the Longdendale reservoirs would be inadequate to meet future demand in the city. He suggested creating a reservoir by combining two smaller lakes - Wythburn and Leathes Waters - in Thirlmere Valley, near Keswick in Cumbria. One of the main attractions to Thirlmere Valley was its height above sea level, because they needed to get water to Manchester by gravity alone. Despite a controversial and lengthy battle with the Thirlmere Defence Association, the scheme was approved by Parliament in 1879 and work began on building the dam and aqueduct. After an eight-year construction project involving 3,000 men, water from Thirlmere Reservoir first arrived in Manchester on the 13th October 1894.

Longdendale Reservoir Chain, Derbyshire

Until the middle of the 19th century, Manchester relied upon local sources of water from wells, rainwater collection systems, rivers and streams. However, rapid urbanisation resulted in increased domestic effluent and industrial pollution and the degeneration of most water courses in and around the city. By the 1830s, Manchester faced a crisis. The health of its inhabitants was at risk owing to the lack of clean water and adequate sanitation, and factory owners demanded ever increasing quantities of water for their growing manufacturing businesses. A solution to Manchester’s water supply problem came when John Frederic Bateman, Manchester Corporation’s water engineer, drew up an ambitious plan to bring clean fresh water from the Peak District into Manchester city and Salford. His vision was to create a chain of seven reservoirs on the River Etherow in the Longdendale Valley, in northern Derbyshire, and for the water to fl ow by gravity to the city. Work began in 1848 and continued until 1884. The introduction of a stable supply of fresh water from the Peak District was instrumental in preventing further cholera and typhoid outbreaks in Manchester. It was the largest and most ambitious municipal water supply scheme built in the world at the time. The chain of reservoirs (since reduced to six) continues to supply Manchester with a vital and stable supply of fresh water.

Sunset over Torside Reservoir Overflow Channel, Longdendale Valley, Derbyshire

Torside Reservoir is the largest in the Longdendale Chain in North Derbyshire. It was constructed between April 1849 and July 1864. This distinctive curved stone overflow channel connects Torside Reservoir to Rhodeswood Reservoir below.

Conduit Bridge, Otter Gear, Lancashire

This triple-arch stone aqueduct carries Thirlmere water across a small valley in Lancashire. The Thirlmere aqueduct is the longest gravity-fed aqueduct in Britain, with no pumps along its 83 mile route (originally 95.9 miles). Water from Thirlmere takes about 36 hours to reach the city. The first phase was completed in 1897, with subsequent phases completed by 1925.

Jubilee Fountain, Albert Square, Manchester

A ceremonial fountain was installed in Albert Square to mark the arrival of Lake District water in Manchester from Thirlmere in 1894. Huge crowds came out to celebrate its arrival, many holding cups to get their first sip of fresh clean water. The fountain was later replaced by this more ornate Jubilee Fountain in 1898. Although many people loved the fountain, some viewed it as a nuisance. The unpredictability of the local wind could lead to a sudden soaking. For a time it was left ‘dry’, until it was eventually moved in the 1920s to Heaton Park. It was not until 1997 that the fountain was returned to the city centre and it was placed once more in Albert Square. The fountain is a visible reminder of the important role that the Thirlmere reservoir and aqueduct played in the growth of the city of Manchester and its continued contribution to this day.

John Butcher, Draw-off Tower, Thirlmere Reservoir

John is a self-proclaimed ‘pipeline anorak’ who has worked in the water industry for 30 years. He is particularly proud of his association with the 1894 Thirlmere Water Scheme. “I started out as a draughtsman updating paper maps of the aqueduct. And now I’ve been a part of the recently completed multi-million pound refurbishment programme to ensure it will continue to supply almost a million people with their daily water needs for another 120 years. I love that the visionary Victorian engineering of the 1890s still enables 250,000 tonnes of water a day to fl ow downhill to Manchester over 100 miles away.

Activated Sludge Plant, Davyhulme Sewage Treatment Works, Trafford

The rapid population growth of the boroughs of Manchester in the mid to late 19th century was placing huge pressures on all aspects of the town’s basic infrastructure. The absence of a regulated sewerage system and the fact that very few homes had even the most basic of fresh water supplies or toilet facilities had resulted in Manchester having one of the highest death rates in the country. Many officials and councillors who had refused to take the necessary action for years began to realise that something needed to be done to improve the health and living standards of the city’s inhabitants. The Davyhulme waste water treatment works opened in 1894 and became famous across the world for its experimental work on the treatment of sewage and wastewater. The pioneering research of Edward Ardern, William Lockett and Gilbert Fowler at Davyhulme resulted in the discovery of the ‘activated sludge process’ – a biological process for treating sewage and wastewater using air, bacteria and protozoa. The activated sludge process is now one of the most widely used for the treatment of sewage and has found application in almost every country in the world. Its discovery was instrumental in the treatment of large quantities of wastewater and ultimately allowed the population of Manchester and urban areas across the world to expand more rapidly. Davyhulme is now one of the largest sewage treatment works in Europe. Where once sewage sludge was loaded on to boats and dumped in the Irish Sea, it is now put through a high temperature treatment process that generates methane gas to provide energy for the site and fertilisers which can be used in agriculture.

Sewage Hoppers, Manchester Shipping Canal

Sewage sludge used to be loaded onto barges on the Manchester Shipping Canal next to Davyhulme Treatment works. The sludge was dumped in the Irish Sea.

Laboratory, Davyhulme Sewage Treatment Works

Blessing Ceremony of Hands Well, Tissington, Derbyshire

The true origins of well dressing are unknown. According to many sources, it developed from a pagan custom of making sacrifice to the gods of wells and springs to ensure a continued supply of fresh water. It was later adopted by the Christian church as a way of giving thanks to God for the gift of water. One theory suggests that the custom began just after the Black Death of 1348-9. Tissington managed to escape the plague and it became the custom to decorate the wells in thanksgiving. Another tradition recalls the severe drought of 1615, when many cattle perished and crops were lost. The five wells of Tissington continued to flow freely and a thanksgiving service was held and the wells were decorated each year in celebration. In the early days, the dressing of wells would have taken the form of simple arrangements of flowers and other natural materials. The tradition of elaborate pictures made primarily from individual flower petals pressed onto clay covered boards seems to date from Victorian times, when there was a desire to revive and enhance old folk traditions.

Hall Well, Tissington, Derbyshire

Maharajah's Well, Stoke Row, Oxfordshire

In the mid 19th century a squire from Ipsden in Oxfordshire, Edward Anderdon-Reade, worked with the Maharajah of Benares in India. One of his many deeds there was to sink a well in 1831 to aid a local community. When Mr Reade finally left the region in 1860, he asked the Maharajah to ensure that the well remained open to the public. A couple of years later the Maharajah decided on an endowment in England. He remembered Mr Reade’s generosity in 1831 and also recalled his stories of water deprivation in his home area of Ipsden and the story of a little boy who was beaten by his mother for drinking the last of the water in their house during a drought. So it was decided that a new well would be sunk at the village of Stoke Row. It was dug by hand to a depth of 368 feet – more than twice the height of Nelson’s Column – and took about a year to build. It was opened officially on Queen Victoria’s birthday in 1864 and became the first of several wells funded in the region by royals and other benefactors from India.

Adelphi Weir, River Irwell, Salford

“The hapless river – a pretty enough stream a few miles higher up, with trees overhanging its banks, and fringes of green sedge set thick along its edges – loses caste as it gets among the mills and the printworks. There are myriads of dirty things given it to wash, and whole waggon-loads of poisons from dye-houses and bleachyards thrown into it to carry away; steamboilers discharge into it their seething contents, and drains and sewers their fetid impurities; till at length it rolls on – here between tall dingy walls, there under precipices of red sandstone – considerably less a river than a fl ood of liquid manure, in which all life dies, whether animal or vegetable, and which resembles nothing in nature, except, perhaps, the stream thrown out in eruption by some mud-volcano.” Hugh Miller describing the River Irwell in his book First Impressions: England and its People (1847)

River Medlock, Central Manchester

Upstream from Manchester the Medlock was crucial for the mills and dye works that lined its banks – it was a source of water and power and an outlet for industrial quantities of sewage and effluent and other unwanted by-products. Fetid and polluted, the Medlock regularly flooded in high rains, spreading filth into slums areas – such as ‘Little Ireland’ – that were built on its banks.

River Irwell, Manchester

“Anybody who stands today in the City of Manchester outside the Exchange Station and looks down at the noisome black water which flows beneath him would find it difficult to believe that any fish, or any other living creature, could ever have lived in what the ‘Manchester Guardian’ has so rightly called that 'melancholy stream’. From many points of view we should all be proud of the River Irwell. It is the hardest working river in the whole of the United Kingdom. On the 50-mile stretch of the River Irwell and its main tributary, the Roach, stand more than 100 cotton mills, in addition to a large number of other industrial undertakings – slipper factories, bleach works, coal mines, tanneries, paper mills and gas works. I think it is true to say that no other inland river has made a greater contribution to the industrial greatness of this country.” Anthony Greenwood, Member of Parliament for Rossendale. House of Commons Speech, 18 April 1950

River Irk, Central Manchester

This Irk was one of the main arteries of early industrial Manchester. By the early 19th century its banks were lined with fulling mills, dye works, chemical factories, abattoirs and tanneries. It was an open drain for both industrial and domestic waste. Friedrich Engels described it in 1845: “At the bottom [of the channel] flows, or rather stagnates, the Irk, a narrow, coal-black, foul-smelling stream, full of debris and refuse, which it deposits on the lower right bank. In any weather, a long string of the most disgusting blackish green slime pools are left standing on this bank, from the depths of which bubbles of miasmatic gas constantly arise and give forth a stench unendurable.” Engels, The Condition of the Working Class in England (1845)

River Irk, Central Manchester

“The Irk, black with the refuse of dye-works erected on its banks, receives excrementitious matters from some sewers in this portion of the town – the drainage from the gasworks, and filth of the most pernicious character from the bone works, tanneries, size manufactories etc. Immediately beneath Ducie-Bridge, in a deep hollow between two high banks, it sweeps round a large cluster of some of the most wretched and dilapidated buildings of the town. The course of the river is here impeded by a weir, and a large tannery eight stories high… towers close to this crazy labyrinth of pauper dwellings. This group of habitations is called ‘Gibraltar’, and no site can well be more insalubrious than that on which it is built.” Description by Dr James Phillips Kay (1832)

River Irk, Collyhurst, Manchester

River Medlock, Manchester

Former site of ‘Little Ireland’, Manchester

‘Little Ireland’ was a slum area with a large poor Irish population which developed along the banks of the River Medlock in central Manchester. It was widely viewed as one of the worst places to live in the city. Houses which were first intended as modest middle class residences had been taken over by industrial workers and there was unplanned, opportunistic building on the space available around and between the factories and mills. Poor ventilation and sanitation led to them being regarded as centres of infectious disease and they became the target of urban sanitary reformers.

Walker’s Croft Cemetery, Victoria Station, Manchester

A pauper burial ground called Walker’s Croft was consecrated next to this site in 1815. Many of those buried there were victims of the typhoid outbreak in 1830 and cholera epidemic of 1831-32. The burial ground was bought in 1839 by the Manchester and Leeds Railway and Victoria station was constructed on top of it. The German writer, Friedrich Engels witnessed the arrival of the railway and recorded his experience: “About two years ago a railroad was carried through. If it had been a respectable cemetery how the bourgeoisie and the clergy would have shrieked at the desecration! But it was a pauper burial ground, the resting place of the outcast and superfluous, so no one concerned himself about the matter. It was not even thought worth-while to convey the partially decayed bodies to the other side of the cemetery; they were heaped up just as it happened, and piles were driven into newly-made graves, so that the water oozed out of the swampy ground, pregnant with putrefying matter, and filled the neighbourhood with the most revolting and injurious gases. The disgusting brutality which accompanied this work I cannot describe in further detail.” From The Condition of the Working Class in England (1845)

Former site of Swan Street Cholera Hospital, Manchester

During the cholera outbreak of 1831-32, there was suspicion of the medical profession, especially among the poor Irish who feared that bodies were being used for dissection by medical students. When relatives opened the coffin of an already buried cholera victim (a four-year-old Irish boy) and found that the head had been replaced by a brick, it confirmed their worst fears. On 2 September 1832 a crowd of up to 3,000 gathered and marched upon the Swan Street Cholera Hospital, demolished parts of the building, broke windows, damaged beds and released many of the patients.

Paul Hindle, Angel Meadow, Manchester

Angel Meadow sits on the edge of Manchester city centre. Its population grew rapidly in the mid 19th century and was predominantly made up of Irish who had fled the Great Famine to find work in industrial Manchester. They lived in appalling conditions, often several families living in a dark and damp cellar. “Angel Meadow certainly did not live up to its name! It was described in the early 19th century as over-crowded, filthy and squalid. With a combination of a poor water supply and a lack of sewers, the area was ripe for the spread of cholera.” Paul Hindle, Senior Lecturer in Geography at the University of Salford for 30 years (retired) and the Honorary Secretary of the Manchester Geographical Society

68 Dean Street, Soho, London

In the early 18th century – when there were virtually no links to common sewers – cesspits, sumps and soakaways were to be found in most large houses across affluent central London and Westminster. Almost all were destroyed or obscured when connections to sewers were installed during the mid 19th century. 68 Dean Street in Soho is thought to be the only early Georgian house left in London where both the family and servant’s cesspit can be seen. Archaeological studies estimate that they were built c.1734 and were in use until c.1862. This family cesspit is located in a basement vault at the rear of 68 Dean Street. The cesspit was connected, via a brick-built, tile-lined chute (since removed), to a family privy located in the back yard above (see next image). There is evidence that the cesspit originally had a brick domed top incorporating an opening to allow it to be emptied occasionally by ‘night soil men’.

Family privy, 68 Dean Street, Soho, London.

Servants' cesspit, 68 Dean Street, Soho, London

This servants’ cesspit is located at the front of the house in a vault underneath the road on Dean Street. It is thought that servants would have used a potty to have transferred their waste to the cesspit. There was also an opening onto the street above to allow servants to wash down the pavement and road in front of the house and drain the water into the cesspit below. Liquids drained primarily into a small early 18th century sewer visible at the bottom of the rear wall. However, when the pit was unearthed in 1997, archaeological investigations appeared to reveal that the bricks had little or no bonding material. This may have allowed some of the cesspit’s contents to disperse into the surrounding sands and gravel. The size and shape of the cesspit is thought to have helped increase the structural strength and prevent collapse from water pressure exerted by the surrounding earth.

Back Yard Privy, at 87 Hackford Road, London

This privy sits in the back yard of 87 Hackford Road, a Georgian terraced house which was home to the artist Vincent van Gogh between 1873 and 1874. It has a distinctive ceramic Sirex bowl dating from the late 19th century and a metal water cistern made in nearby Kennington, south London. The design and sophistication of outdoor privies evolved considerably across Britain during the late 19th and early 20th century. Many thanks to James and Livia Wang for allowing access for photography

House of Parliament, London

For centuries, the River Thames played the role of dumping ground for all of London’s various wastes – human, animal, and industrial. By the start of the 19th century, enough waste and pollution had accumulated there to make it the most contaminated river in the world. Although the deterioration of the Thames was noticeable before the onset of the Industrial Revolution, it was a heatwave during the summer of 1858 that finally brought it to the attention of the government. That summer, all of the sewage in the Thames began to ferment – centuries of waste began to release a noxious and offensive stench. Members of Parliament tried at first to ignore the stink and continue their sessions without agreeing to any drastic plans of reform. They knew full well that there was no easy solution to clean up the river and rid it of its smell. Instead they installed heavy curtains – soaked in chloride and lime – in the windows of the Houses of Parliament, in an attempt to relieve their own senses of the stench but also through a misguided fear that disease was spread through miasma or ‘bad air’. Ultimately it was the proximity of the Houses of Parliament on the River Thames that meant that MPs could not ignore the problem and forced them to take immediate action. Within a record 18 days, a bill was created, passed, and signed into law that would refurbish the entirety of the River Thames and lead to Sir Joseph Bazalgette’s visionary sewerage system that is still in use today.

Old London Bridge, by Dutch painter Claude de Jongh (1632)

Old London Bridge, constructed between 1176 and 1209, served London as a river crossing until it was demolished in 1831 after the opening of ‘New’ London Bridge. During more than 600 years Londoners used the river flowing under the bridge to take away all kinds of waste, including sewage. Over the years various public and private latrines were constructed to hang over the river, so that their contents could be discharged directly into the water below. Credit: Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund

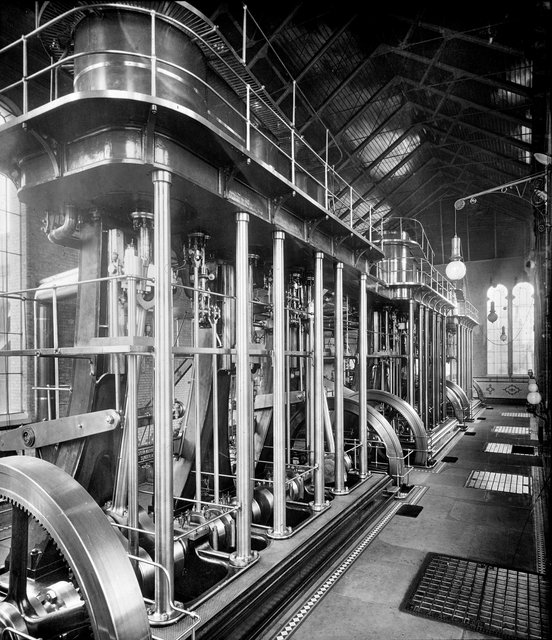

Beam Engine House, Crossness Pumping Station, London

Crossness Pumping Station was designed by Sir Joseph Bazalgette as part of his visionary sewerage system for London. It was o fficially opened by the Prince of Wales in April 1865. There were two halves to Bazalgette’s sewerage system, north and south of the River Thames. The broad principle was to get the sewage to the east of London, store it in reservoirs until high tide and then release it. On each side of the Thames, three intercepting sewers diverted sewage away from the river and lead it, by gravity where possible, or by pumping where necessary, towards the outfalls at Beckton on the north and Crossness on the south. At each outfall, reservoirs enabled the sewage to be stored until high tide and then discharged into the river. The Beam Engine House at Crossness is constructed in Romanesque style and features some of the most spectacular ornamental Victorian cast iron-work to be found today. It contains the four original pumping engines, which are possibly the largest remaining rotative beam engines in the world, with 52 ton flywheels and 47 ton beams. The old steam engines were decommissioned in 1913 and replaced with diesel engines, which were in service until Crossness was closed in 1956. The Crossness Engines Trust was set up in 1987 to restore this unique part of Britain’s industrial heritage.

Central Octagon and Main Beam Floor, Crossness Pumping Station, Abbey Wood, London

Morelands and Riverdale building c.1900

Reproduced with kind permission of The London Museum of Water and Steam and Thames Water.

Morelands & Riverdale Building, Hampton WaterWorks, London.

The Hampton Waterworks were formed in 1855 in response to the London cholera epidemics of the early 19th century. The water engineer Joseph Quick had the idea to extract water away from the polluted tidal Thames up river from the Teddington and Molsley locks. Quick created a series of filter beds next to the river and three new pumping stations, for three different water companies. Water was pumped by steam-powered engines up to distant reservoirs and other pumping stations in the capital through large, buried brick culverts and later cast iron pipes. As London’s population grew, demand for water rapidly increased. As a result the Hampton site was expanded by Sir James Restler, the Chief Engineer to the Southwark and Vauxhall Water Company. The Morelands building (far left) was completed in 1886 and the Riverdale building (right) followed in 1897. Both buildings contained huge steam-powered rotative engines fed around the clock with coal. The engines pumped a large proportion of the water to London and were some of the most efficient designs of their time. In 2012 Thames Water sold the Morelands and Riverdale buildings. It still owns and operates all the water filter beds seen in front of the buildings.

Riverdale Engine House c.1900

Reproduced with kind permission of The London Museum of Water and Steam and Thames Water.

Riverdale Engine House, Morelands-Riverdale, Hampton, London

The Riverdale engine house became operational in 1897 and ceased pumping in the 1960s. It is currently being refurbished by Blackbottle, the new owners of the Morelands and Riverdale buildings. “The intention for the site’s future is to create a small scientifi c community which will be inspired by its surroundings. Many modern laboratory facilities where some of our best minds work are unfortunately lacking in inspirational spirit. So the poignancy of benefi cial scientifi c research taking place in these fi ne buildings – that were originally created to improve London’s public health – is not wholly accidental; they simply seem to suit this use. The buildings are infused with the Victorian spirit of virtuosity, innovation and ambition and the scale and detail of the original architecture eff ortlessly lends itself to a new 21st century use. The pump houses and boiler houses had extraordinarily broad roof-spans for the time, which provided vast, open plan interiors and since they originally contained many large moving parts, they are intensely lit with enormous windows and lanterns. So it’s possible for us to create lighter, glazed buildings within buildings, set-back from the original walls and windows to provide the sense of heritage, space and plentiful daylight that aid bright ideas.” Belu, designer for Morelands-Riverdale

Basement of Riverdale Engine House

Lydia Zigomo, Head of East Africa Region, WaterAid. Fleet Sewer, London

London’s sewers were a magnificent feat of civil engineering which, despite being built more that 150 years ago, continue to serve London’s inhabitants. Fair and equitable access to good sanitation is something most of us take for granted; we can’t imagine a situation in which some citizens have access to taps and toilets while others don’t. Lydia Zigomo, WaterAid’s Head of East Africa Region knows only too well that this is not the case for too many of the world’s poorest people. Having worked previously as a human rights lawyer, Lydia, who is originally from Zimbabwe, now champions equity and inclusion at WaterAid to ensure that everyone has sustainable access to safe water, sanitation and hygiene education. Increasingly WaterAid’s work focuses on those who are most marginalised and vulnerable to unsafe water and sanitation: women, girls, children in and out of school, and elderly and disabled people. “Seeing the incredible work that went into building the original London sewer network confirms to me that it takes vision, investment, political will and long-term planning to provide vital sanitation for all. We take for granted the fact that our waste is taken away from our homes, schools and offices to be dealt with and treated. Everyone should have similar access to toilets and good sanitation.”

Sir Tony Robinson, actor, writer, broadcaster and historian

My family have lived along the River Lea for over 300 years. This may sound a long time, but in fact the Lea has been an artery of London life since the Romans settled here. It begins as a trickle in Luton and eventually joins the Thames at Docklands. It’s a cunning, complicated river which fractures into complex networks of smaller waterways. It has a proud industrial history starting way back before the Tudors with a system of massive medieval tidal mills. By the twentieth century there were factories all along its banks, and modern industries too like electronics. Ferguson and Amstrad started here – indeed some historians have called it London’s ‘Silicon Valley’! But with all this development going on, the river itself was getting filthier. People ignored it: it was as if it no longer existed. It was known locally as ‘The West Ham Dump’. The word Lea gives its name to Luton and Leyton. It actually means ‘bright’, but when I was a child it fl owed a diff erent colour every week, depending on what the factories were pumping out. Eton College set up a charity here for the local communities, encouraging working class children to adopt a healthier lifestyle. They held a swimming contest every Christmas – the fastest child won a turkey. It was the unhealthiest competition imaginable! The Olympics brought life back to this area – London 2012 truly was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to transform the valley and the river itself. But we can’t become complacent about our water systems or take a clean, safe water supply for granted. The Lea still has massive pollution problems, and a huge act of human will is required to solve them. We have a responsibility to look after our ‘Bright River’ for generations to come, and to do what we can to make sure others around the world can enjoy similar benefits from their rivers and streams.

Hugh Bonneville, actor and WaterAid Ambassador

“A sewage works in south-east London may not sound like the most glamorous of landmarks but Crossness Pumping Station is something special. Once described as a ‘cathedral on the marsh’, its unremarkable exterior conceals truly spectacular Victorian ornamental cast ironwork and mighty pumping systems, which are currently being restored to their former glory by a group of dedicated volunteers. Crossness is a testament to the groundbreaking engineering that played a significant role in improving the health of Victorian Londoners and helped create the thriving capital city of today. Back in the 19th century, London’s sewage ran through the streets, carrying deadly diseases into the very river on which its population depended for drinking water. The problem reached crisis point in the ‘Great Stink’ of 1858, when the smell of untreated human waste and industrial effluent became unbearable for MPs in the chamber at Westminster. They fi nally took action, commissioning Sir Joseph Bazalgette, Chief Engineer to the Metropolitan Commission for Sewers, to develop a solution for the sanitation crisis. In just eight years, the London sewer system was complete and waste water south of the river was channeled underground to Crossness, where it was stored in covered reservoirs until high tide before being discharged into the River Thames and away from the city. The result was a life-saving development that ensured proper sanitation across London, reducing contaminated water sources and helping to eliminate water-borne diseases, such as cholera, which regularly plagued the city. As an Ambassador for WaterAid, I’ve learned how many of the problems faced by Londoners 150 years ago remain a daily reality for millions of the world’s poorest people. Yet history has proved that with political will and straightforward engineering it is possible for everyone everywhere, to have access to clean water and improved sanitation. If it could be achieved in London in the 1860s, then we can definitely make it happen today, right around the world.”